Note: This article was originally posted on Medium. Check it out there, if you want!

I love games. It’s proven that games help our psychological state, encourage social connectivity, and generally relieve stress. Much has been written about the effect of games in our lives, including some truly insightful work by game designer Jane McGonigal.

Games combine the powerful forces of story and play to convey emotion, entertain, and can even teach new skills. Adding game mechanics like achievement, collection, socializing and discovery gives games their unique attributes and appeal — simply called gameplay.

New products apply gamification liberally as a key stategy. Gamification is a cliché, sure, but when done well users are able to engage with powerful mechanics. Profile completeness, points and badges are just the beginning — even the network effect has its roots in game mechanics.

The Dungeon Master holding court.

The Dungeon Master holding court.

Classic tabletop strategy games like Dungeons & Dragons have used these same concepts for decades. A dungeon master (or game master) assembles a group and creates a living story — called a campaign — for their players to explore.

The game master is charged with:

- Creating a rich world that supports the campaign

- Guiding the players in ways that align with their unique character skills

- Obeying and interpreting the rules of the game

…and also providing snacks. Overall, the game master exists to facilitate the story and achieve these goals in engaging, creative ways.

Product Management as World Building

Product managers can apply game mechanics to the work of product development, but more importantly they can apply the goals of a game master to the work they do each day.

A product is a created world. It has characters, pitfalls to avoid, challenges to overcome, and a story to complete. By using these game master strategies, a product team can build amazing things and have fun while doing it.

Macro Arc, Micro Arcs

The Adventure Zone podcast has redefined tabletop storytelling in podcast form.

The Adventure Zone podcast has redefined tabletop storytelling in podcast form.

Griffin McElroy, host of the The Adventure Zone podcast, laid out this concept when explaining his rationale and inspiration behind their game. When he wrote their campaign, he focused solely on the overall campaign arc. He knew that the “macro-arc” of the story had to be intact in order for it to make sense. The payoff at the end meant certain key elements of the story had to happen, or else the game was over.

When writing the campaign, Griffin was less concerned with the small, micro-arcs within the story. There are many of them, and there’s too many to script out or rely on in order to keep the game moving. Rather, he exposes various possible edges of these micro-arcs to his players and allows them to explore at their will.

Product Vision

Like a game master, a product manager has to understand the vision and arc of a product. A few key questions to ask:

- Where must the product go in the future to be successful?

- What market forces (competitors, clients, etc) are at work that must be overcome?

- How will it best serve key users?

- How will the product change the world in six years?

- Most importantly, what does the team and company unwaveringly believe in?

These questions should establish the guide rails the team needs when building the product. Outside of these factors (which may not change quickly or at all!), be flexible to new ideas and features of a product.

Open World

Skyrim actually procedurally generates infinite new side quests.

Skyrim actually procedurally generates infinite new side quests.

In an open world game, the playable character is presented with big objectives and lots of side quests. It’s up to the player to choose which way to go and which quests to complete or ignore.

As a result, there may be whole components of a story that go unnoticed by players. A game master shouldn’t hold these plot points as precious, but let them go in service of the greater story being experienced by the players.

A game master has to prepare possible paths inside the story and hold playable characters responsible for interacting with them. The players are a key variable in the storytelling process, who provide new story elements that a game master has to react to.

User Appropriation

When a product gets into the hands of actual users, unexpected things tend to happen. Users may find a feature confusing, or they may even use it differently than it was designed. Of course, a team may release a feature that no one uses.

During these moments, a product team could choose to be hostile towards users and mock them for their misuse. They could champion the features they worked so hard on, and force a user to engage with the feature. This happens often through marketing efforts, re-routing users to certain pages and even redesigning other features so they include the underused new functionality.

Instead, a product team should listen to what their users are saying, watch what they’re doing, and make refinements that enable the appropriated behaviors and actions. Product managers are in service of the product, which is in service to the user. Treat user feedback as gold, and incorporate it as a key component of planning the product’s future.

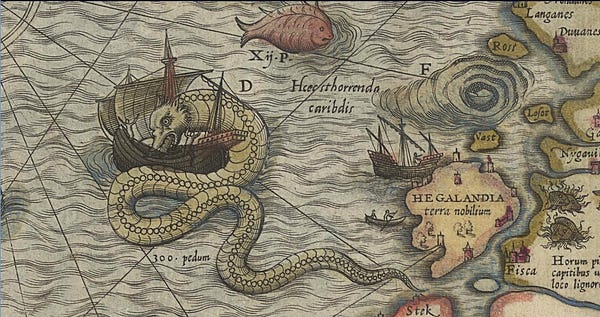

Here Be Dragons

Here Be Dragons just meant “unknown” on the map, not necessarily danger.

Here Be Dragons just meant “unknown” on the map, not necessarily danger.

A game master knows what information to reveal to their players.

Sharing information is vital: players have to find clues in order to make decisions. However, knowing too much enables a player to avoid risky situations (and thus, spoils the fun).

Friends at the Table does this masterfully. They share maps with Roll20 to create a remote tabletop experience. Maps grow, iterate over in-game generations, and aren’t ever complete.

Draw maps, but leave blank spaces.#FriendsAtTheTable

— FatT Wisdom (@FatT_Wisdom) October 2, 2016

Friends at the Table Wisdom.

The game master, Austin Walker, is obsessed with clocks. Clocks are little game markers that count up or down, and the hands on the clocks get moved when major actions happen in the game. These clocks are tense reminders that small actions taken by the players have potentially huge repercussions later down the road.

Iterative Design

Leave space in the product. Navigation, page layouts, and text/content will change as a product team learns and builds more. Leave space for the product to grow and expand. If there’s no more space, consider breaking out the product into companion applications.

The first released version of a feature should exist to answer three questions:

- Does it solve an actual problem?

- Can our users actually use it?

- What should we add to the feature now?

Every feature has a roadmap. It grows and evolves over time, especially in response to these questions. A product team should make plans to create more value and complexity in a feature accordingly. However, the first release (or even just usability tests) of a feature can inform it further for the future. Don’t get too hung up on future plans, but leave space in the roadmap and the product for the plans to unfold.

Leveling Up

A Dungeons & Dragons Character Sheet

Playable characters receive experience points (XP) upon completing certain quest elements or defeating enemies. They learn new spells, pick up helpful items, and activate effects over time.

At key XP levels, users gain levels which improve their overall abilities and characteristics. As the campaign progresses, the challenges the players face becomes more difficult. These two forces must be in balance for the game to be enjoyable. No one likes an impossible challenge, but a game that’s too easy to beat won’t be fun to play for long.

User Onboarding

A good product should guide a user through the act of using it. Using tools like Intercom’s Campaigns easily allow a product to “speak” to a user as they take necessary steps to engage with the product.

As a user engages with a product, what are new features or new messages that can be delivered to them? Is it possible to sequence a user’s actions by adding more complexity and additional features once they “unlock” them with their own experience?

Pay walls are easy ways to achieve this, in the SaaS world. Test a “pro” tier model that locks up key features or additional services per month, and segment different audience groups by what they’re willing to pay. These passionate users may have different needs from a free or lower priced tier, which allows a product team to better prioritize a roadmap.

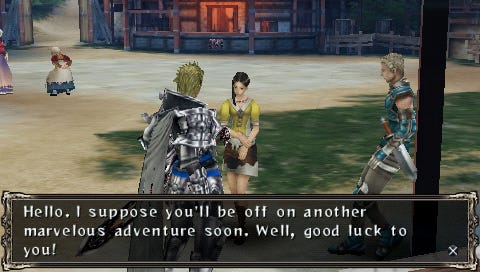

Non-Playable Characters

NPCs act as signposts and delivery mechanisms to guide the player.

Non-Playable Characters (NPCs) are characters played by the game master. They’re more than just exposition or set-dressing: they help move the story, guide the players, and include all enemies the players encounter during their campaign.

A good NPC doesn’t solve the problem for the players, but helps them discover the solution. They may provide a valuable resource or item in a moment of need, or even just raise a flag to point in a new direction.

Humanizing the Product

Tools like Intercom, HubSpot and chatbots are quickly introducing a human element into the onboarding and engagement activities of modern products. Bots and messengers can help provide in-app signage, guideposts and helpful tips to users. They shouldn’t replace a human interaction, but can do wonders for helping remove roadblocks for users.

These bots can easily turn sideways if the interactions aren’t planned properly. They should be directional, helpful, and include an escalation path to real humans.

Steal from Everywhere

Luke, use a constitution saving throw!

Luke, use a constitution saving throw!

Inspiration is all around. While Dungeons & Dragons has inspired many games (looking at you, Skyrim!), storylines within campaigns can contain elements from all sorts of cultural touchpoints. Great campaigns incorporate real-world events, follow the trajectory of movies, books, and more. Look for patterns in story arcs, find things that fit the campaign. Weaving in aspects of amazing stories and ideas only makes a campaign stronger.

No Really: Steal from Everywhere

Inspiration really is all around. Great products and apps launch every day and ideas can come from everyday interactions. Look for patterns, find what works, and find ways to incorporate similar patterns. Don’t copy for the sake of copying, but look for what solves problems that the product is currently struggling with.

And Most Importantly…

Write a story you believe in with people you care about.

Write a story you believe in with people you care about.

Games like this require a team. This can’t be done alone, and if someone isn’t contributing, they tend to get written out of the story. The same is true for building product. Be humble, be helpful, enable others to do great work, and the story will write itself.